Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

Pipestone Cashes In by Solving Wastewater Problem with Drinking Water Treatment

From the Fall 2022 Waterline

Quarterly Newsletter of the Minnesota Department of Health Public Water Supply Unit, Waterline

A complete list of feature stories can be found on the Waterline webpage.

The southwestern Minnesota city of Pipestone went through a decade-long odyssey of water issues and emerged triumphant with a holistic solution.

The city of 4,200—known for pipestone quarries considered sacred to many tribal nations—had operated for years with chemical addition at four wells, ranging in depth from 500 to 700 feet. Even though the wells were relatively deep, a rock ledge within 75 feet of the ground made the area vulnerable to contamination of its aquifers. Although contamination from the surface wasn’t a problem, by 2009 Pipestone had levels of naturally occurring radium and gross alpha emitters approaching the legal limits.

“We were right on the threshold. One time it would tip [the limit] and the next time it wouldn’t,” said Joel Adelman, who first started working for Pipestone in 1995 and has been its water/wastewater supervisor since 2004. The city was addressing the radionuclides at the same time it was being contacted by both the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) and Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) over another issue.

“It was our chloride discharge,” explained Mayor Myron Koets. The city estimated that about 75 percent of the chloride contribution coming into its wastewater plant was from the brine used for regenerating home water softeners.

Pipestone has raw-water levels of about 40 grains (680 parts per million) of total hardness. Residents needed their own softeners to reduce the levels, but the in-home treatment was contributing to wastewater problems with high levels of chloride, which are toxic to aquatic species.

Joel Adelman, Myron Koets, and Jeff Jones over the clarifier

Pipestone looked beyond what to do at the wastewater plant; it focused on treatment of the drinking water that would include softening at the plant, reducing or eliminating the need for in-home softeners. In addition to addressing many issues related to health, the environment, and the aesthetic quality of the water, this approach paved the way to funding mechanisms related to both water and wastewater.

“They were one of the first systems in the state to deal with chlorides by treating the drinking water,” said Chad Kolstad, the coordinator for the MDH Drinking Water Revolving Fund (DWRF). In addition to a DWRF loan, Pipestone received a point source implementation grant to deal with chlorides. “That’s why funding came into the balance so nicely,” Kolstad added regarding the additional money made available.

The sand and anthracite filters

Adelman toured water treatment plants in the region to see what other communities were doing as the city explored options with the engineering firm of Bolton & Menk Inc. of Mankato, Minnesota. Reverse-osmosis (R-O) treatment was considered, but the high rate of water loss through R-O would have made it unfeasible. “There wasn’t enough capacity on the wastewater side if we have any infiltration issues,” said Adelman.

The process finally chosen for a new water treatment plant incorporated aeration, softening, and filtration. Construction began in 2017 on a 1.15 million-gallon-per-day plant on the northern edge of Pipestone. Water from the wells (which includes a fifth well drilled as part of the project) is pumped to the top of an aerator, comprised of numerous pipes through which the water flows. The aerator oxidizes iron and manganese and also strips carbon dioxide from the water, facilitating the softening that follows.

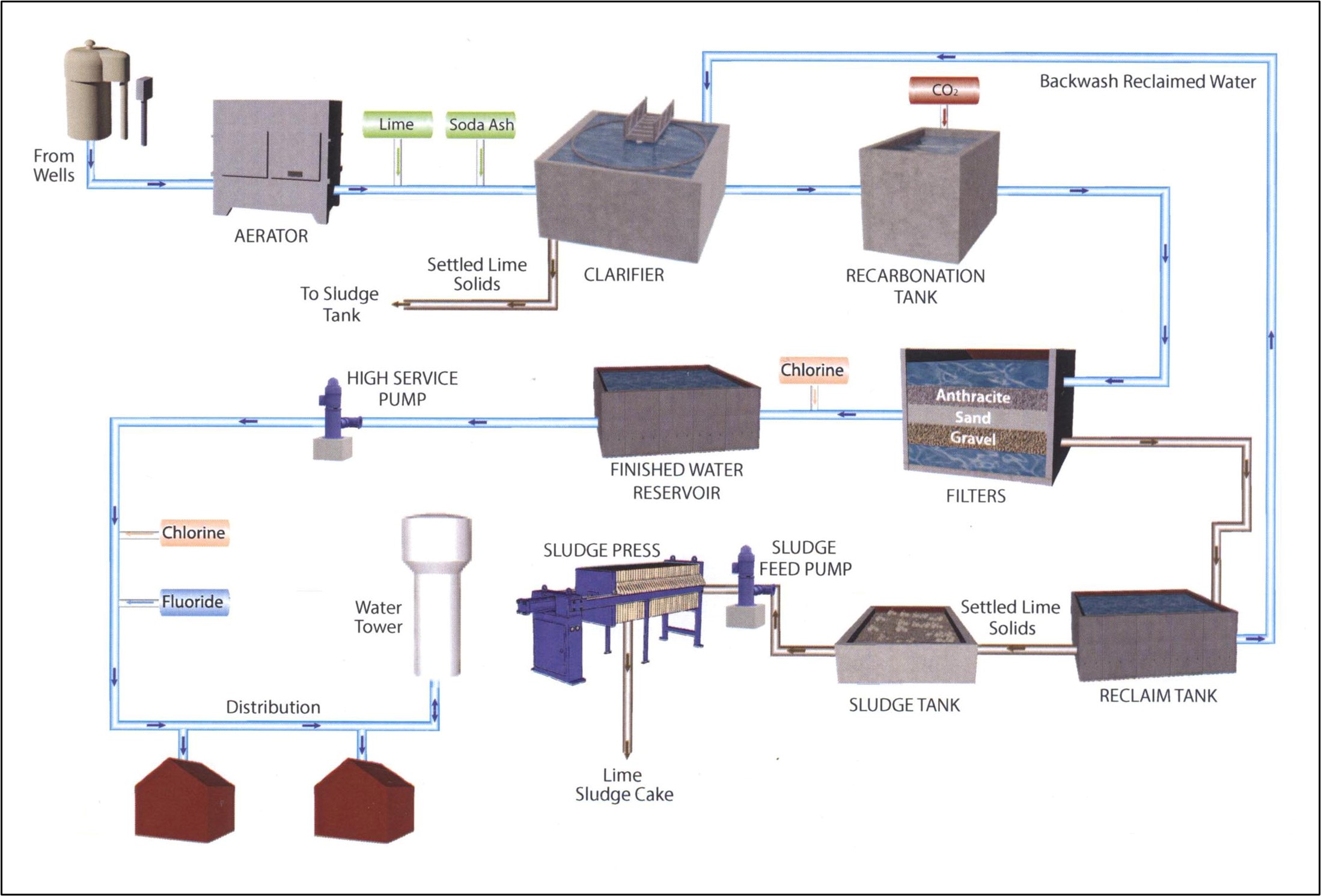

A schematic of the treatment process at the Pipestone water facility. Below is the sludge press in the new plant.

The lime and soda ash used for softening cause calcium carbonate and magnesium hydroxide to form precipitates that are removed in the clarifier and gravity filters. Lime also raises the pH of the water, which helps with the softening reactions. Following the clarifier, water flows to the recarbonation tank, where carbon dioxide is added to the water to adjust the pH of the water to a more neutral level.

After the recarbonation tank, the water flows by gravity into three 12x14 foot filter basins consisting of 15 inches of anthracite and 15 inches of sand. The filters remove the iron and manganese, which were oxidized to form rust particles in the previous stages, and any remaining calcium and magnesium precipitates that were not removed in the clarifier.

The material trapped by the filter beds is removed by backwashing. The backwash water flows to 60,000-gallon reclaim tanks and is held to allow particles to settle out. The clear water is returned to the beginning of the process, and the settled solids are pumped to the sludge holding tank.

The filtered water flows to a 450,000-gallon clearwell and reservoir. Chlorine is added before water reaches the reservoir and again as the water is pumped to the distribution system. High service pumps send water to two water towers and finally out to the residents.

As the plant went on-line in 2019, Pipestone worked with citizens to adjust or remove their home softeners, which allowed the city to meet its limits on chloride discharge.

The $15.4 million project was funded by a DWRF loan of $8.4 million and a point source implementation grant of $7.0 million from the state. The inability of the Minnesota legislature this year to approve a bonding bill was a disappointment for city officials, but Pipestone was still able to greatly limit rate increases to finance the project. “It’s the cost of having good water,” said city administrator Jeff Jones.

For its big-picture vision and innovation, Pipestone received an Aquarius Award through the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Drinking Water State Revolving Fund program for its excellence and leadership in the financing and construction of a new water treatment plant to address public health and environmental issues.

“By taking a holistic approach to solving their problem, the city was able to meet both their public health and environmental standards far more cost effectively,” said Kolstad.

MDH engineer presented Mayor Koets with the EPA Aquarius Award at the We Are Water exhibit when it was in Pipestone in 2021.

Go to > top.