Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

Minneapolis Uses Microtunneling for Water Main below the Mississippi River

From the Winter 2020-2021 Waterline

Quarterly Newsletter of the Minnesota Department of Health Public Water Supply Unit, Waterline

A complete list of feature stories can be found on the Waterline webpage.

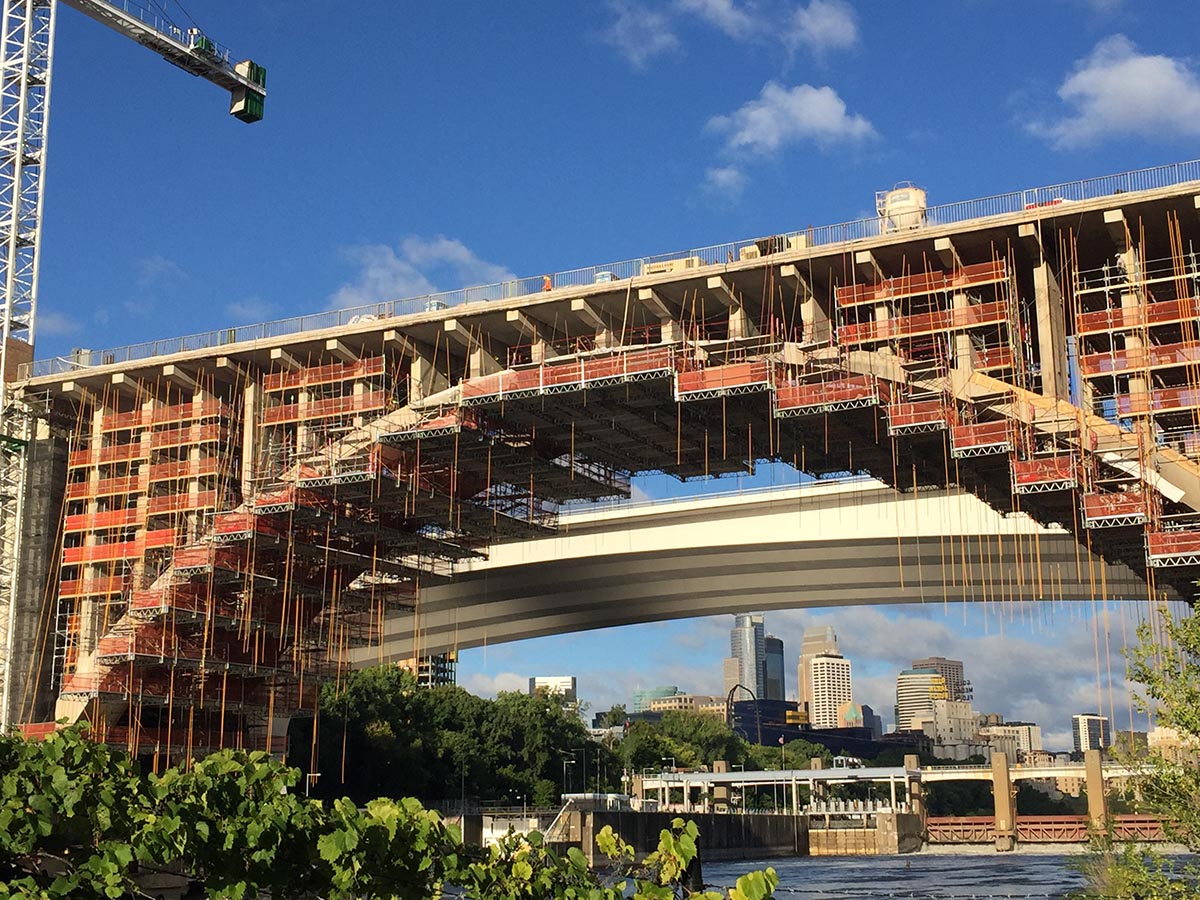

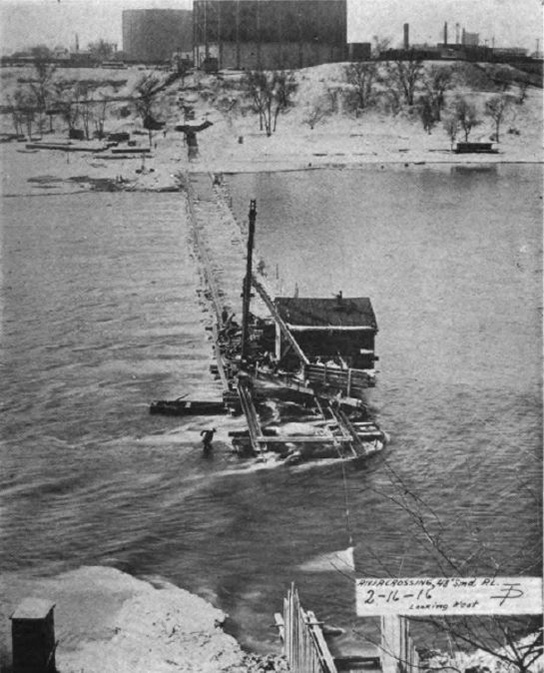

The Tenth Avenue Bridge in Minneapolis (shown in the lower portion of the 1959 photo above) was the path for a 54-inch water main from the 1940s until recently. More than 50 years later, the main was removed as the bridge went through renovations. Minneapolis Public Works Water Treatment and Distribution Services Division, rather than going back to its old way, is using an emerging technology. The 1959 photo shows the configuration and street schemes of the Seven Corners area of the West Bank prior to the 35W bridge. The Washington Avenue Bridge, replaced in the latter part of the 1960s, is downstream around the bend. The photo below, taken in September 2020, shows the rehabilitation of the Tenth Avenue Bridge. Beyond it are the 35W bridge, the lower St. Anthony Falls lock and dam, and the downtown skyline.

Seven of the largest water mains carrying drinking water in Minneapolis cross the Mississippi River at various locations in the city. Some of the water mains are suspended from bridges that span the waterway. Others, including two near the Minneapolis Public Works Water Treatment and Distribution Services Division (WTDS) treatment plant and river intake in Fridley, are in trenches in the riverbed.

Just downstream of downtown is a water crossing that has transitioned from a trench to a bridge and now to something new. Even before the Tenth Avenue Bridge was completed in 1929, the city had a riveted steel waterline in a shallow trench in the riverbed, connecting the area known as West Bank to southeast Minneapolis in the vicinity of the University of Minnesota.

|

|

A photo from 1916 taken from the eastern bank of the Mississippi River (left) shows the construction of a trench for a waterline to be placed in the river bed. A 1917 photo (right), taken from the west bank of the river, shows the riveted steel pipe being submerged.

The city replaced this line with a 54-inch welded steel main above the arches in the 1940s. What prompted the change isn’t certain although it is speculated that it was because of a desire by the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers to dredge the river for a deeper channel to allow navigation farther upstream. The Upper Minneapolis Harbor Development project, which eventually included the construction of two locks and dams by St. Anthony Falls, was already underway. (In 2015, the upper lock and dam – which lifted barges and boats 50 feet to get beyond the falls – was closed to stop the spread of invasive carp.)

With a renovation planned for the Tenth Avenue Bridge two years ago, Minneapolis WTDS looked at another way of maintaining a cross-river waterline. The exposed waterline was subject to freezing if shut down, and it experienced repeated expansion and contraction from cold and heat, especially since the pipe had no expansion joints. The pipe’s exterior coating was deteriorating, and the main was corroded from runoff carrying road salts that would leak through expansion joints on the bridge.

Rather than hang another main above the river, the city decided to go back down, this time all the way below the Mississippi with a tunnel 30 feet below the riverbed employing modern microtunneling technology. Remote-controlled pipe jacking has become popular for urban construction since it is environmentally friendly and causes less disruption than traditional open trenching. It is also an ideal way to get a waterline from one side of a river to the other.

The microtunneling machine is lowered into a pit on the east bank. Driven by hydraulic jacks, the machine has cutting heads to drive through the soil and a conical crusher to grind the material into smaller particles, which are removed with a slurry and brought to a chamber on the surface. An operator in a trailer on the ground steers the machine with the help of a laser-guidance system.

“You get only a few chances to do something different,” said Glen Gerads, director of water treatment and distribution for Minneapolis Public Works.

Getting the water main out of the elements means a much longer life expectancy for the pipe. Peter Pfister, an engineer for Minneapolis WTDS and the project manager for the venture, pointed out that this also calls for a careful adherence to quality control because of the difficulty of making repairs to a pipe buried under a river.

The hydraulic jacking frame in the sending pit on the east bank.

The project began in 2019 with the construction of shafts on each side of the river. The sending pit is on the east bank (actually on the north side at this bend of the river). Its excavation was facilitated by the freezing of the groundwater, which allowed the contractor to dig through frozen soil. It is approximately 900 feet from the target, the receiving pit in Bluff Street Park on the west bank (the southern side). The pits are as deep as 130 feet and large enough to fit the tunneling machine.

Lowered by a crane into the sending pit, the laser-guided microtunnel boring machine was controlled from the top of the shaft to emerge at the proper spot. As the boring progressed, a bentonite slurry was pumped from the surface to ports inside the tunneling machine to its exterior front and sides, providing cooling and lubrication for the motor. “The slurry then picks up removed soil and rock and carries it back up to the surface, where the removed material is separated from the slurry by a shaker-sieve apparatus,” explained Pfister. “The filtered slurry is then cycled back to the tunnel machine.”

Penetration by the tunneling machine in the working shaft. The metal collar is referred to as a thimble, where a rubber static seal and a rubber inflatable seal are situated such that when the machine and casing pipe are inserted into the thimble and the inflatable seal is inflated with air, it constricts around the pipe, keeping the groundwater from coming into the shaft.

Penetration by the tunneling machine in the working shaft. The metal collar is referred to as a thimble, where a rubber static seal and a rubber inflatable seal are situated such that when the machine and casing pipe are inserted into the thimble and the inflatable seal is inflated with air, it constricts around the pipe, keeping the groundwater from coming into the shaft.

A 60-inch permalock casing pipe followed the tunneling machine, which took about two weeks to reach its destination on the west bank. Then the sections of main will be lowered into the shaft and propelled by a hydraulic jacking frame, each of them welded together. Pfister said the length of each section was only 20 feet, its length constricted by the diameter of the pit.

The receiving pit in Bluff Street Park on the west bank of the Mississippi River.

Gerads said that the life-cycle costs made this a more viable solution than to hang the main from the bridge again. “We’re going back to where we were, and we won’t have to worry about it for a couple hundred years.”

Work on the $16 million project progressed on schedule – even the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic did not slow it down as the city and contractors employed precautions to keep workers safe – with expectations for the new water main to be on-line in the spring of 2021.

Upriver a bit from the site of the Minneapolis waterline project is a portion of the bed of the Mississippi River. This area became accessible when the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers lowered the river level by 12 feet for a few days in October 2020 in order to inspect the upper and lower dams and locks at St. Anthony Falls. The exposed river bottom is mostly on the east side of the river by the Stone Arch Bridge (above). Spectators were able to go down wooden staircases along with a bit more trekking to get to the riverbed. The shadow of the bridge looms over some of the merry wanderers (below).

Go to > top.