Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

Minneapolis Distribution Crews Maintain Critical Infrastructure

From the Fall 2011 Waterline

Quarterly Newsletter of the Minnesota Department of Health Public Water Supply Unit, Waterline

A complete list of feature stories can be found on the Waterline webpage.

|

| The city of Minneapolis is cleaning and lining more than 39,000 feet of its distribution system this summer. One of the projects is along Johnson Street in northeast Minneapolis. |

Minneapolis Water Works has been the subject of international attention and acclaim with its ultrafiltration treatment plant, which opened in 2005. The plant was called “one of the most advanced water treatment systems in the world” that marked “a sea change in the treatment of drinking water” by Robert D. Morris in his book, The Blue Death: Disease, Disaster, and the Water We Drink.

Staying out of the spotlight but doing work that is just as critical is the distribution arm of the utility. Its 1,000 miles of pipe, a lifeline to supply the city with its most precious resource, is hidden beneath the surface, leaving residents, when they hear the word “infrastructure,” to think of roads and bridges, important components to a community but not near as vital as what they don’t see.

That’s fine with Marie Asgian, superintendent of water distribution. “If you can take us for granted,” she says, “we’ve done our job well.”

History

Minneapolis first started pumping water from the Mississippi River for fire protection in 1867. A few years later the city pumped water into a small number of homes and businesses, establishing a drinking water supply. Personal consumption rose quickly with the convenience of piped-in water as the distribution network grew.

By the turn of the century Minneapolis had built settling basins and reservoirs in Columbia Heights and eventually added a treatment plant on the site. To increase storage capacity the city added three water towers in some of its elevated neighborhoods. The Kenwood tower, to the west of downtown Minneapolis, was built in 1910; the Prospect Park tower, off University Avenue in southeast Minneapolis, was built in 1913, and, two years later, the city purchased an existing water tower, the Washburn tower in an area known as Tangletown off 50th Street and Nicollet Avenue in south Minneapolis, and extended the height of the tower by 25 feet for additional pressure.

Minneapolis increased the pressure in 1931 in this part of the city by demolishing the Washburn tower and building a new one. By this time, the utility had added another treatment plant, in Fridley along the Mississippi River.

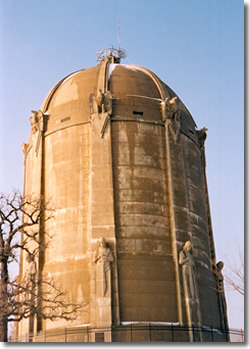

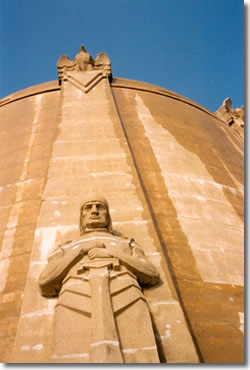

The Washburn, Kenwood, and Prospect Park water towers still stand and have been designated as city landmarks although none is used for water storage any more (the Washburn tower lasted the longest in its original function, holding water into the 2000s). Each tower is distinct. Prospect Park residents use the “witch’s hat” feature of their tower as a means to decorate the tower on Halloween. The Washburn tower has a number of adornments, including 16-foot-tall “guardians of health” mounted on pilasters, along with eagles at the base of the dome.

|

|

| From left to right above: the Prospect Park tower and the Kenwood tower. Below: the Washburn tower along with a closer look at one of the “guardians of health” and the eagle at the base of the dome. | |

|

|

Today

Rehabilitation or replacement of the distribution system is an ongoing task for Minneapolis. At the current rate of funding, approximately 1 percent of the distribution system is renovated each year.

Pipes installed after the early 1970s are made of ductile iron that comes from the factory with cement lining on the inside. However, this makes up only about 25 percent of the system. Most of the distribution system consists of unlined cast iron, and well over half of it was constructed prior to 1930.

“It’s not that old pipe is bad pipe,” said Asgian. “If it’s in proper bedding, it will last 200 years. It’s all about the bedding. With good granular material that drains away from the pipe, the likelihood of a break is low.”

Minneapolis had 29 water main breaks in 2010. Asgian said they won’t put a cement lining in a pipe that has a failure history; if anything, they will install a structural liner, a process that involves cleaning the inside of the pipe, pulling a sock liner injected with epoxy resin through it, and robotically drilling out the service taps after the resin has cured. This creates a new pipe within the existing pipe. Pipes that are structurally sound will be cleaned with metal scrapers prior to the installation of a cement mortar lining.

Cleaning and lining of pipes has aesthetic benefits, reducing rust and complaints of red water, but Asgian points out the other effects, such as improved flow for fire protection and prevention of nitrifying bacteria that can reduce the disinfection residual.

Two factors govern the selection of project locations. One is an opportunity to perform work in conjunction with street construction. The other is the magnitude of the problem. Minneapolis crews are working with a contractor, Heitkamp, Inc. of Watertown, Connecticut, on a project along and around Johnson Street in northeast Minneapolis, an area that has had many problems with red water. City crews maintain control of the water during the project, which includes installation of temporary water lines from hydrants from adjacent blocks as they take hydrants out of service on the block currently under construction.

Heitkamp performs the rehabilitation work, using metal scrapers to clean the pipe and then installing a cement mortar lining. The pipe in this area was installed in 1906. Although the cleaning and lining of a total of 12,150 feet of pipe, divided into two phases, takes fewer than two weeks, the overall project—which includes excavation and associated work—began in late April and will be completed in mid-October.

The total project cost of $612,000 is in line with the typical cost of $50 to $60 per foot for cleaning and lining. Asgian says replacement costs are about $300 per foot.

The northeast Minneapolis project is one of seven that the utility is performing in 2011. Overall, city distribution crews will clean and line nearly 39,000 feet of pipe at a cost of $2.3 million.

|

|

| Crews from Minneapolis Water Works shown at the distribution yards in southeast Minneapolis and on the job site in northeast Minnesota. Shown in the lower right are Mark Ebert, Bob Ervin, and Marie Asgian. | |

|

|

Of Interest

Minneapolis Ultrafiltration Plant

Go to top