Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

A Look at the Other End

We focus on Water Supply. What happens next?

From the Fall 2018 Waterline

Quarterly Newsletter of the Minnesota Department of Health Public Water Supply Unit, Waterline

A complete list of feature stories can be found on the Waterline webpage.

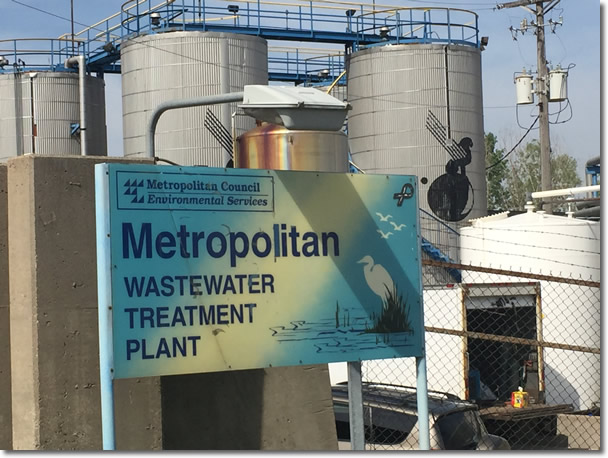

Most of the articles in the Waterline focus on water supply and making the water safe to drink; the other end of the process is just as important, and recently employees of the Minnesota Department of Health had the chance to tour the Metropolitan Wastewater Treatment Plant. To accompany the photos and description of the plant is a story, "Clear Water Obsession," that was written by the editor of the Waterline more than 25 years ago, when he was a reporter for Construction Bulletin magazine. This story appeared in a special anniversary issue, Construction Bulletin: The First 100 Years:

It wasn't that long ago that a stroll along the Mississippi River produced an unsightly sight: raw sewage, huge mats of it floating downstream like a dead turtle.

For years, residents relied on the Mississippi to ingest whatever they put into it, using its natural biological abilities to process and assimilate the foreign materials. In this, they hardly differed from other cities in the United States located adjacent to major waterways. Rivers, lakes, oceans, and other bodies of water can be remarkably proficient in purifying waste. The large quantity of clean water diluted the sewage; the natural movement of the water carried the sewage away from the cities; and naturally occurring microorganisms in the water consumed organic wastes.

But, as was the case elsewhere, the problems of turning a river or lake into an open sewer of human and industrial waste eventually took its toll. As the water became murkier, recognition of the hazards became clearer.

Locally, the health implications with the lack of adequate sanitation became cause for concern as far back as the mid-1800s. Although sewers began to replace backyard-disposal practices in the 1870s, the sewage still ended up in the same place: the Mississippi River.

Somehow people were still able to ignore the brown and oily texture the river was taking on as it began to live up to one of its many nicknames: the "Big Muddy." Spring floods were the savoir as the flushing action of the high water scoured the banks of the Mississippi, removing the past year's deposits of sludge and providing an adequate amount of natural cleansing.

But the opening of the Ford Dam in 1917 slowed the current of the water above the dam, reducing the purging action of the spring flooding. Sludge deposits quickly formed, and by dawn of the Roaring Twenties, an estimated three million cubic yards of sewage sludge was settling-much of it clearly visible on the surface-in the waters upstream from the dam. No longer could residents close their eyes-or their noses-to the fouling of their waters.

Once again, health concerns were the catalyst for action. The Minnesota State Board of Health proclaimed the Mississippi River a "public-health nuisance," prompting the appointment of a drainage commission and the eventual formation of the Minneapolis-St. Paul Sanitary District in 1933.

Two years later, work began on a wastewater treatment plant on Pig's Eye Island, a few miles downstream from downtown St. Paul. With the completion of the Pig's Eye Plant in 1938, the Twin Cities became the first major metropolitan area along the Mississippi River to treat its sewage before dumping it into the water. Its effects were immediate and dramatic. The floating rolls of sewage virtually disappeared, and levels of dissolved oxygen, a critical water quality indicator, rapidly improved. From a health standpoint, the implications of the treatment were also readily noticeable.

The Pig's Eye Plant was hailed as an engineering marvel and attracted thousands of visitors to tour the facility. Many were engineers from other parts of the country, hoping to learn the secrets of the Pig's Eye processing as they planned similar practices for their community.

The art-deco administration building (above) was part of the original Pig's Eye Plant, which now covers more than 100 acres (below).

As the region continued to grow, more treatment plants were necessary. Today, the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area has 11 such plants, all under the jurisdiction of the Metropolitan Waste Control Commission (MWWC), established by the Minnesota Legislature in 1969.

The original Pig's Eye Plant has hardly been overshadowed by the addition of others. Although it has been renamed (now called simply the "Metro Plant"), it remains the largest wastewater treatment facility serving the Twin Cities. It treats 225 million gallons of wastewater per day, about half the wastewater generated in the state and 80 percent of that by the Twin Cities. The combined residential-industrial-commercial population served by the plant is more than two million people.

The treatment process at the Metro plant essentially mimics the natural ability of the water to cleanse itself as some particles are removed through sedimentation and others are ingested by microbes, although at a greatly accelerated rate.

The first process takes place in primary treatment. Sand, grit, and the larger solids in the wastewater are separated from the liquid through the use of screens, settling tanks, and skimming devices. Approximately half of the pollutants are removed in this phase.

Following primary treatment, a biological process takes place to remove most of the remaining pollutants. Air is infused in the wastewater to stimulate the growth of microbes-bacteria and other organisms-that then consume the waste materials. In the process, ammonia is also converted into non-toxic nitrates.

The water is then separated from the organisms and solids, which settle to the bottom of the separation tanks, where it is either incinerated, placed in landfills, or used as a soil conditioner in agricultural areas. At some treatment plants, this sludge serves as a fuel to produce energy.

The water is disinfected with chlorine-which is later neutralized to keep it from harming aquatic life-to kill any harmful bacteria that remain and, finally, released into the Mississippi River.

The Metro Plant is a gravity-fed treatment system. The progressive phases are slightly lower in elevation than the previous ones, allowing water to pass through the plant and finally into the river without the need for pumps.

In addition to the treatment plants, the MWWC owns and maintains 500 miles of interceptor sewer pipes (sewers that intercept the flow of the original city sewers) that carry sewage from the producers to the treatment facilities.

Construction on the Minneapolis East Interceptor, 40 feet below northeast Minneapolis. The largest tunneling project in Minnesota up to that time, the interceptor was completed in 1991.

The sewers have been the focus of increasing attention in recent years. When the city sewers were first built late in the 19th century, they were designed to carry both storm water and sewage to the river. The interceptor sewers, however, are designed to handle only normal sewage flows. Heavy rains or rapid snow melts can increase the flow in the city sewers to the point that some of the combined flow-run-off and wastewater-bypasses the interceptor sewers and flows directly into the river.

In 1984, it was estimated that 4.6 billion gallons of combined untreated sewage and stormwater flowed into the Mississippi annually.

The cities of Minneapolis, St. Paul, and South St. Paul began work to provide separate storm and sanitary sewers. Their initial schedule did not call for complete separation until 2025. In 1985, however, the Minnesota Legislature mandated an accelerated 10-year schedule for the three cities, with total separation of the sewers finished by the end of 1995.

Although treatment practices of some type have been in existence for many years, it has been only in the last quarter-century that national standards on water quality have been set. Because of the leading role Minnesota has taken with regard to wastewater treatment, the MWWC has had no trouble in adhering to contaminant limits established with the passage of the Clean Water Act of 1972 and subsequent amendments to the Act.

Construction never ceases on the MWCC's system of plants and sewers. Flood protection projects completed in 1975 provided for an earthen dike and concrete floodwall to an elevation nearly eight feet above the water levels during the record floods of 1965. An effluent pumping station was added in 1977. These improvements paid dividends in June of 1993 following periods of heavy rains. As the swollen Mississippi covered surrounding lowlands, including the downtown St. Paul airport, the Metro Plant continued operations to treat sewage.

The enhanced quality of water manifested itself in a strange way a few years ago. On a warm evening in June of 1987, a bumper crop of mayflies hatched in the Mississippi River near the Minneapolis-St. Paul airport. Attracted by the lights from nearby traffic, they converged on a bridge over the river, leaving Interstate 494 more than a foot deep in insects. The highway had to be closed and snowplows called out to clear the mayflies.

The good news in the story was that mayflies are signs of clean water. Despite the inconvenience they caused, their spawning was evidence that the state of the Mississippi River has indeed come a long way.

Go to top