Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

DWRF Funds the North Shore

From the Winter 2023-2024 Waterline

Quarterly Newsletter of the Minnesota Department of Health Public Water Supply Unit, Waterline

A complete list of feature stories can be found on the Waterline webpage.

From south to north (or more specifically, southwest to northeast), Duluth and Two Harbors are the first two Minnesota cities to draw water from Lake Superior. With an Ojibwe name of Gitche Gumee (just ask Henry Longfellow, or Gordon Lightfoot for that matter, if you don’t believe it), Superior is the largest freshwater lake in the world. In addition to Duluth and Two Harbors, it is the water supply for Beaver Bay, Silver Bay, Grand Marais, smaller cities along the north shore. As the two largest cities supplied by the big lake, Duluth (above left) and Two Harbors (above right) have also been regular recipients of money from the state Drinking Water Revolving Fund (DWRF) and both have been putting it to good uses lately.

Duluth - Conquering the city

Nearly $4 million ($3,857,531 to be exact) of DWRF money has helped Duluth install new pumps at its booster station, a structure that goes back to the 19th century and that is flanked by a 14-million-gallon reservoir that is young by comparison, having been rebuilt in 1922.

Duluth has a lake-to-hill geographic profile. The first few inland blocks are flat, but the topography quickly becomes hillside, rising abruptly and steeply. For much of the city’s history, an incline served residents needing to go back and forth in an up-and-down manner.

Lake Superior is approximately 600 feet above sea level, the lowest part of Minnesota. The elevation change between the utility’s intake and adjacent treatment facility on the lake is about 280 feet to the booster station. From there the water travels upward through two other reservoirs and two other pump stations, eventually climbing 950 feet above Lake Superior to the Highland tower, the highest point in Duluth’s water system, supplying Duluthians along the way as well as the consecutive systems of Hermantown and Rice Lake. In all, Duluth has eight major pressure zones and a handful of smaller ones.

Duluth’s Aaron Soderlund said the new pumps are only the fourth set in the history of the booster station. The three pumps, he explained, usually run one at a time at 3,300 gallons per minute (gpm). They can get up to 5,000 gpm with two pumps running but rarely do. “The problem with getting up to those flow rates is our pressures,” Soderlund added.

The pumps and surge tank in the Duluth booster station.

The pumps are on the same spots as the previous ones although the new pipes are underneath the building. Another change was the addition of a surge vessel with a bladder tank. Soderlund said they considered the need for a quick shutoff of the pumps in case of a power interruption. “We had some issues in the upper end of this zone, where we would have negative pressure, so the surge vessel is to handle the surge coming back from the stations to alleviate those problems.”

The booster station, shown in the 1930s, had a gas lantern on the front. The mounting is still visible behind Corey Mathisen, Sabrina Sutter, and Chad Kolstad of the Minnesota Department of Health and Aaron Soderlund of Duluth.

The pump project began in early 2022 and went on-line in stages. A challenge encountered along the way was with two suction lines, one coming in off the street and the other directly from the reservoir. Just outside the booster station is an original valve, which hooks up to the station. More than 130 years old, the valve didn’t work. A diver from AMI Consulting Engineers of Superior, Wisconsin, went into the reservoir to plug a 20-inch intake line to allow for the installation of a new valve.

“We needed to close the valve to put in our suction piping for the new pump,” said Soderlund. “We couldn’t close the valve to isolate off the reservoir to do our work within the station.” The diver put in a ball to plug the intake line long enough to put in the new valve and then complete the suction piping to a new pump. Soderlund said that during the six-to-eight hours it took, “The only thing we had from emptying the 14 million gallons out of that reservoir was that plug.

“That was nerve wracking to say the least.” The challenges surmounted, Duluth completed the work in 2023.

The city’s incline to elevate people was phased out with the coming of new-fangled contraptions such as the automobile. But the transport of water upward is still performed with the same methods that have served Duluth well for more than 100 years.

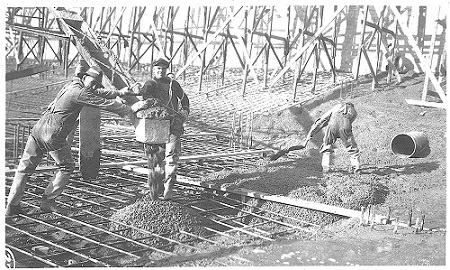

Installation of the 20-inch suction pipe in 1922 and a look at it from within the reservoir a century later.

Two Harbors - The project that keeps on giving

With DWRF money allocated in 2015 with the rehabilitation of a building housing high-service pumps, Two Harbors continued to benefit from the funding in replacing its chlorine contact facility several years later.

Located about 25 miles northeast of Duluth, Two Harbors came together from the communities of Agate Bay and Burlington, each of which has a bay formed by a southern-jutting promontory.

Two Harbors has had water facilities on Burlington Bay for more than 70 years with a power plant existing on the site even before that. A chlorine contact tank was added in 1958 and a filtration plant about 20 years later. High service pumps, which were replaced in 2016, have been around at least as long as the contact tank.

Bolton & Menk, Inc., began working with Two Harbors in 2016 with the rehabilitation of the high-service pump building. During the project, leaking water was discovered from the chlorine contact tank. Brian Guldan of Bolton & Menk said they installed a drain tile as a temporary fix and put a complete replacement of the tank on their to-do list.

It began getting done a few years later, starting with the demolition of the parking lot south of the existing chlorine contact tank. Space restrictions didn’t allow for construction of the new tank until at least part of the lot was removed. “They are building half of the new one,” said Guldan in the fall of 2023. “The new one will go on-line and get tested, and then the old tank will be demolished and the project completed.” Even with one tank at a time during construction, the flow rates can be adjusted to ensure proper contact time.

After the old chlorine contact tank is removed, they will build a second tank next to the new chlorine contact tank, giving the plant two independent tanks with pump chambers to allow for half the tank to be taken out of service for maintenance and still have the capability to produce water at half the capacity.

Above: Dan Foster and Brian Guldan of Bolton & Menk flank Chad Kolstad of the Minnesota Department of Health atop the intake structure on Burlington Bay of Lake Superior. Below: Construction on the chlorine contact tank.

The water treatment facilities have the bay and Lake Superior as a scenic backdrop. The previous contact tank partially blocked the view of the water for nearby residents, who were thrilled to learn that the new structure will be lower, affording an unobstructed vista.

Not just neighbors are enjoying the view. The treatment plant is south of Lakeview Park, which has a trail that is popular with visitors, leading to questions of how to keep people off the new contact tank. One night, Guldan discussed the situation with Chad Kolstad of the Minnesota Department of Health and Luke Heikkila, then the city’s water superintendent. Heikkila said, “Why don’t we turn it into a lookout?”

After Kolstad said he had no problems with the idea, Heikkila turned to Guldan and said, “Make it happen.”

The trio sketched a plan on a napkin for the trail to have access, including a handicapped-accessible ramp, to the top of part of the tank. A railing will separate the lookout from the part of the tank with the hatches. “This way there is a spot to direct people to,” said Guldan.

Two Harbors’s water treatment plant has three gravity filters with silica sand and anthracite. Chlorine is added to the water coming in from the lake, and then poly aluminum chloride for the rapid mix, although the raw water normally meets turbidity standards even without chemical addition. After flocculation, the water is filtered and sent to the chlorine tanks.

Elevation differences in Two Harbors aren’t as dramatic as in Duluth. From the plant the water goes through two booster stations in series to a 1.25-million-gallon tower in the northern part of the city and then to a second tower, this one 100,000 gallons, to the northwest. In addition to the booster stations and towers, Two Harbors has seven pressure reducing stations.

“The project that keeps on giving,” is how Guldan describes the work that began in 2016 and is encompassing the upgrade of the building with the high-service pumps, filter rehabilitation in the treatment plan, the chlorine contact tank, a new maintenance garage, and pipe and valve replacements. “This project will take care of their major needs for 20 years.”

The flocculation basins(above) and filters (below) in Two Harbors.